By Abdul-Hakim Shabazz

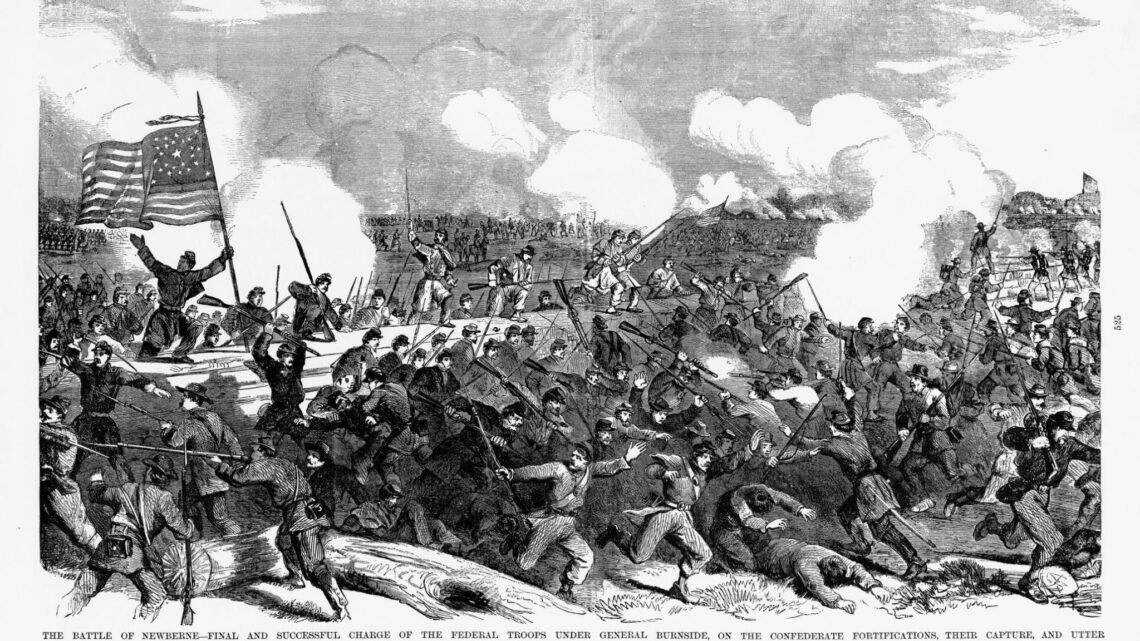

In July 1862, Confederate forces crossed the Ohio River and briefly seized the town of Newburgh, Indiana, just downriver from Evansville. It was not Gettysburg. It was not Antietam. It was a raid — part bluff, part audacity — and it shocked Hoosiers who believed the river was a protective boundary between them and the war. Geography, it turned out, was not immunity. The line they assumed secure was simply the next line waiting to be tested.

The significance of Newburgh was less military than psychological. It demonstrated that conflict does not respect comfort zones. It exposed how quickly assumptions collapse when pressure is applied.

More than 160 years later, Vanderburgh County is offering a modern variation on that lesson. This time the crossing is not cavalry but compliance forms. The raid is not mounted soldiers but political paperwork. And the shock, while less cinematic than cannon fire, may be just as revealing.

Ken Colbert, a conservative activist previously declared “not in good standing” and barred from party participation through 2029, filed to run as a Republican delegate to the state convention. He signed the required state form attesting that he complied with his party’s candidate requirements. In another political era, that filing would likely have triggered a credential challenge, some heated debate, and perhaps a ruling from party leadership.

Instead, it produced a misdemeanor citation. That escalation is not insignificant.

Political parties traditionally manage internal disputes through internal mechanisms. Credentials committees, party chairs, and election boards are the usual referees. The stakes can be high, the rhetoric sharp, but the machinery remains political rather than criminal. When a dispute over party standing moves from parliamentary procedure to potential prosecution, it reflects a shift in enforcement posture.

And this shift is not occurring in isolation.

What we are witnessing across Indiana is less a polite intraparty disagreement and more a full-blown political food fight — something closer to Animal House than Edmund Burke. Republican senators who deviated from leadership on congressional redistricting now face organized primary challenges. Greg Goode. Travis Holdman. Jim Buck. Ron Alting, etc.

Alting’s independent streak — once described as pragmatism or institutional experience — is now viewed in certain circles as deviation requiring correction. Challengers position themselves as purer alternatives, even when their own public histories have required what might generously be described as strategic polishing before filing. It is remarkable what a determined rebranding effort can accomplish.

These contests are not spontaneous grassroots uprisings fueled purely by outrage. They are about controlling the process at the most granular level. It is how Micah Beckwith secured the Republican nomination for lieutenant governor. It is how Diego Morales built his path. And that model continues to animate insurgent strategy today. Win the grassroots. Control the delegates. Shape the nominations. Reshape the caucus.

Add one more layer to that equation: if insurgent candidates win enough primaries — and if delegate slates shift accordingly — the math inside the Senate changes. And when the math changes, leadership becomes vulnerable. That includes Senate President Pro Tem Rod Bray. Each individual contest may appear procedural in isolation. Together, they form a strategy.

Whether the fight unfolds on a convention floor or at the ballot box, this broader climate has heightened scrutiny of the mechanics of candidacy itself. Earlier this year, after questions from Indy Politics, the Secretary of State released a list of special deputies who administered candidate oaths. In another instance, a seemingly minor signature became the focal point of a ballot eligibility controversy. What once seemed like technical minutiae — oaths, signatures, filing formalities — now carry strategic weight.

Paperwork is no longer a clerical issue, it’s a tactical one.

In that context, the Colbert filing is less about one activist’s eligibility and more about the evolving posture of enforcement. Colbert maintains he believed he was eligible to run. Party officials insist the prohibition was clear and continuing. A court may eventually determine whether his certification was knowingly false. But the larger signal is already evident: the instruments of party discipline are sharpening.

None of this guarantees a shift in Senate leadership. Incumbent leaders possess relationships, institutional knowledge, and political durability. But the sustained effort to reshape the caucus makes clear that the leadership question is not hypothetical. It is active.

Newburgh in 1862 did not decide the Civil War. But it demonstrated that Indiana was not insulated simply because it preferred to believe so. Likewise, a delegate filing in Vanderburgh County will not single-handedly determine the future of the Indiana Senate. It does, however, make one thing clear: the struggle over control has moved from rhetorical disagreement to tactical engagement.

The river is no longer a boundary. And anyone assuming that these skirmishes will quietly resolve themselves has not studied history — or politics — very carefully.

All ain’t quiet on the southwestern front.