by Abdul-Hakim Shabazz, Esq.

Every time Indiana politics gets itself twisted in a knot, someone inevitably waves a hand toward Illinois and says, “Well, they do it!” as if the Land of Lincoln is the gold standard for cartographic integrity. I say this with love, as someone who actually worked in Illinois politics and lived inside one of its more creatively drawn districts before moving to Indiana in 2004: if we are now taking legal cues from Illinois, that may explain quite a bit about why we are in this mess.

Because here’s the truth: Illinois redraws because it has to. Indiana is redrawing because someone in Indianapolis thinks a certain Florida resident will clap his tiny hands. Those are not remotely the same.

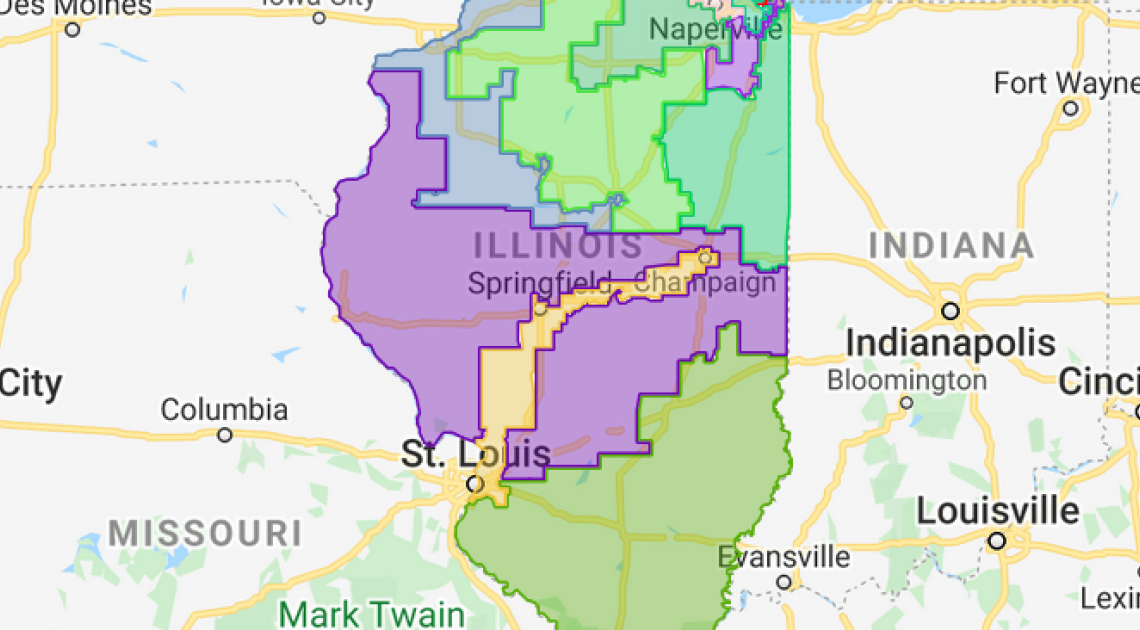

Back when I lived in central Illinois, during one of its more infamous redistricting cycles, Champaign and Springfield were placed in the same congressional district—an arrangement that, on paper, made about as much sense as pairing Beyoncé with Kid Rock. Other than me, the University of Illinois, and the state capitol, Champaign and Springfield don’t share much besides highways and weather patterns. Yet there we were, thrown together like a political arranged marriage crafted by a cartographer with a Sharpie and a grudge.

People love to point to that “snake district” as proof that Illinois draws absurd, self-serving maps. And yes, the shape was absurd. But the shape alone never told the whole story. What critics misunderstand—and what anyone who has spent time in Illinois politics understands intimately—is that Illinois draws weird-looking districts because the law requires it, not because legislators wake up dreaming of abstract art.

The Political Backdrop People Forget

Before we get into the legal tornado that forces Illinois to redraw, it helps to see the political arc:

Illinois congressional delegation:

• 2000: 10 Democrats, 10 Republicans (20 seats → reduced to 19 after Census)

• 2010: 11 Democrats, 8 Republicans (19 seats → reduced to 18)

• 2020: 13 Democrats, 5 Republicans (18 seats → reduced to 17)

Illinois lost seats twice. Federal law doesn’t politely suggest a redraw—it demands one.

Indiana congressional delegation:

• 2000: 6 Republicans, 4 Democrats (10 seats → reduced to 9)

• 2010: 6 Republicans, 3 Democrats

• 2020: 7 Republicans, 2 Democrats (remained at 9)

Indiana hasn’t lost a seat since 2000. No forced redraw. No VRA pressure. No court supervision.

Illinois has turbulence.

Indiana has stability—and is voluntarily choosing chaos.

Illinois: Redrawing by Legal Obligation

Illinois is repeatedly dragged back into the redistricting process because of federal law, court orders, and demographic realities.

Before the 2010 Census, Illinois had 19 congressional seats. Afterward, it dropped to 18. After 2020, it dropped again to 17. You cannot fit 19 members into 17 seats without rewriting the map. Math is still undefeated.

Then there’s the Voting Rights Act, especially in Chicago and the Metro East—the Illinois side of St. Louis, home to one of the largest concentrations of Black voters outside Chicago. If the Chicago courts don’t get you, the Metro East will. Under Section 2 of the VRA, states must avoid diluting minority voting strength where large, geographically concentrated minority populations exist.

This isn’t theoretical. The Seventh Circuit in Ketchum v. Byrne, 740 F.2d 1398 (7th Cir. 1984) forced Illinois to redraw Chicago ward boundaries after finding minority vote dilution. Later cases involving Latino representation repeated the cycle. And when Illinois flirted with using estimated Census data instead of final numbers, courts nudged them—well, shoved them—back to the drawing board.

Illinois redraws because the law leaves them no choice.

Indiana: Redrawing Because It Wants To

Now contrast that with Indiana.

We have none of those triggers. No lost seats. No Voting Rights Act cases. No equal-protection rulings. No court orders.No lawsuits requiring remedial maps.

No deadlines blown. We completed our normal redistricting in 2021 on time and without judicial interference.

So why are we here in 2025, drawing mid-decade maps like Texas did under Tom DeLay?

Not because of law. Not because of population change. Not because a court demanded it.

We are doing it because national political pressure—the gravitational pull of Mar-a-Lago—whispered that it would be helpful for 2026 and 2028. The Supreme Court warned about this exact thing in LULAC v. Perry, 548 U.S. 399 (2006), noting that mid-decade redistricting done strictly for partisan advantage invites “excessive manipulation.”

Yet here we are, volunteering for the kind of trouble most states only get into by judicial subpoena.

The Real Contrast

Illinois’ odd shapes are the byproduct of legal necessity—Census shifts, VRA mandates, and significant minority population clusters in Chicago and the Metro East. Indiana’s new shapes—whatever they turn out to be—are the byproduct of political convenience.

So the next time someone says, “Illinois does it,” remind them:

Illinois is rebuilding after a legal tornado.

Indiana is bulldozing the house because someone thinks the feng shui might poll better in a primary.

As someone who lived inside one of those Illinois snake districts, let me assure you: the shape may have been ugly, but the legal foundation was solid.

Indiana can’t say the same.

And that should worry anyone who cares about what actually makes “a state that works.”

Abdul-Hakim Shabazz is the editor of Indy Politics and an attorney licensed in Indiana and Illinois.